Introduction

Data structures organize information in programs. Every language ships nearly the same core set of structures, even if they appear under different names or with slightly different APIs.

This catalog exists to help you build a cross-language mental model of those types. Once you understand each structure’s core properties and trade-offs, choosing between “list vs map vs set” stops being guesswork and starts being deliberate.

What this is: a catalog of fundamental data structure types. For each type, you’ll see:

- What it is

- Why it exists (what problem it solves)

- Where it appears across popular languages

- When its properties make it the right choice

What this isn’t: a deep dive on performance tuning and system design. For that, see Fundamentals of Data Structures, which focuses on using these structure types effectively in real systems.

Why this catalog matters:

- Language familiarity – Reading code in a new language gets easier when you can map

dict↔map↔HashMapin your head. - Property awareness – Knowing “this structure has O(1) lookup but no order” prevents nasty surprises in production.

- Structure selection – You stop guessing between lists, maps, and sets and start choosing based on operations.

- Debugging clarity – “This request is slow because we used a list instead of a set” becomes an obvious diagnosis.

- Interview preparation – Most data structure questions boil down to “which type and why?”; this catalog gives you those mental models.

Type: Explanation (understanding why structure types exist and when to use them). Primary audience: beginner to intermediate developers who can already write small programs but want a cross-language mental model of data structure types and their use cases.

Prerequisites: What You Need to Know First

Before exploring this catalog, you should be comfortable with these basics:

Basic Programming Skills:

- Code familiarity - Ability to read code in at least one programming language.

- Variable concepts - Understanding of how data is stored and accessed.

- Basic operations - Familiarity with creating, reading, and modifying data.

Software Development Experience:

- Some coding experience - You’ve written programs that store and process data.

- Language exposure - Experience with at least one programming language’s standard library.

You don’t need to master Big O notation or do formal proofs. This article emphasizes structure properties and language appearances, using light complexity labels to aid comparisons.

See Fundamentals of Data Structures for effective data structure use in software—performance, reliability, system design. See Learn Asymptotic Notations for learning asymptotic notations.

What You Will Learn

By the end of this article, you will understand:

- Why fundamental data structures exist and their purpose.

- Where each structure appears across language ecosystems.

- The core properties that define each structure type and why they matter.

- When to select each structure based on the problems you’re solving.

- How to recognize structure patterns in real code.

Use this article when: You need to understand data structure types, recognize them across languages, learn their purposes, or choose the proper structure for a problem. It serves as a catalog focused on recognition, language mapping, and use cases.

Use Fundamentals of Data Structures when: You need to understand how to use data structures effectively in software—performance optimization, reliability patterns, system design implications, and real-world usage patterns.

How to use this guide:

- New to data structures? Read Sections 1–4 in order.

- Need a quick reference? Jump straight to the section for the structure you’re using.

- Debugging performance? Use Section 8: Choosing Structures and the Troubleshooting section.

What Data Structures Actually Do

Data structures organize memory information. Programs store data, input, results, and settings.

Data structures determine:

- How data is arranged - In sequence (arrays), by relationships (trees), or by associations (hash maps)

- How data is accessed - By position (arrays), by key (hash maps), or by traversal (trees)

- The optimum operation - Different structures optimize different operations

Data structures organize data: arrays are shelves, hash maps are catalogs, and trees are charts. Each simplifies some operations but complicates others. Understanding trade-offs helps choose the best structure for each problem.

The Unifying Mental Model: Three Axes of Structure Choice

All data structures answer one fundamental question: which operations must be fast? Every structure optimizes different operations by making different trade-offs. Understanding these trade-offs helps you choose the proper structure.

All data structures optimize certain operations through trade-offs. Understanding these helps in selecting the appropriate structure.

The three axes of structure choice:

Access Pattern - How do you need to access data?

- By position (index)? → Arrays

- By key/name? → Hash maps

- By priority? → Heaps

- By relationship? → Trees/Graphs

Update Pattern - How do you need to modify data?

- At ends only? → Stacks, Queues, Deques

- In the middle? → Linked lists

- Anywhere? → Arrays (with shifting cost) or Hash maps

Relationship Pattern - How are elements related?

- Sequential (no relationships)? → Arrays, Lists

- Key-value associations? → Hash maps

- Hierarchical (parent-child)? → Trees

- Network (many-to-many)? → Graphs

The key insight: Every structure balances operations: arrays offer quick access but slow insertions, hash maps enable fast lookups but lack order, and trees provide hierarchy with slower searches.

When choosing a structure, ask: “Which operations dominate my use case?” Then pick the structure that optimizes them.

Section 1: Understanding Fundamental Structures

What makes a structure fundamental

A fundamental data structure appears in most programming languages because it solves a common problem. These structures are so essential that language designers include them in standard libraries or core language features.

Fundamental structures share these characteristics:

- Universal need - They solve problems that appear in most programs.

- Language support - They’re built into languages or provided in standard libraries.

- Clear properties - They have consistent behaviors across implementations.

- Practical utility - They’re used often in real-world code.

How structures appear in languages

The same structure may appear under different names or with slight variations:

- Arrays might be called “lists,” “vectors,” or “slices” depending on the language.

- Hash maps might be called “dictionaries,” “objects,” “maps,” or “associative arrays.”

- Sets might be built-in types or library classes.

Despite name differences, the fundamental properties remain consistent. Recognizing these helps identify structures across languages.

Section 2: Linear Structures

Arrays and Lists

What they are: Ordered sequences of elements accessed by numeric index.

Why they exist: Arrays exist because programs need to store sequences where position matters. When you need “the 5th item” or want to process items in order, arrays give you direct access by position, solving the “I need item at index X” problem efficiently. Contiguous storage means elements sit next to each other in memory, allowing the computer to calculate any element’s location instantly: address = start_address + (index × element_size). This is why array access is O(1).

Mental model: Picture an array as a single row of numbered lockers—you can jump directly to locker #5 without checking lockers 1-4 first.

wtf

Core properties:

- Ordered - Elements maintain insertion order.

- Indexed access - Elements accessed by numeric position (0, 1, 2, …).

- Contiguous storage (for arrays) – Low-level arrays store elements in adjacent memory locations; many high-level “list/array” types use a contiguous array of references internally.

- Variable length (for dynamic arrays) – Many modern languages provide dynamic array types (

list,ArrayList,vector) that can grow or shrink; low-level fixed-size arrays still exist. - Homogeneous or heterogeneous - May contain same-type or mixed-type elements depending on language.

Where they appear:

- Python:

list-[1, 2, 3](maintains insertion order, can contain mixed types) - JavaScript:

Array-[1, 2, 3](sparse arrays possible, length property tracks highest index) - Java:

ArrayList,Array-new ArrayList<>()orint[] arr(ArrayList is dynamic, arrays are fixed-size) - C++:

std::vector,std::array-std::vector<int> v(vector is dynamic, array is fixed-size) - Go:

slice,array-[]int{1, 2, 3}(slices are references, arrays are values; slices are more common) - Rust:

Vec,[T; N]-vec - Ruby:

Array-[1, 2, 3](can contain mixed types, negative indices supported)

Common operations:

- Access by index:

arr[0] - Append element:

arr.append(x)orarr.push(x) - Insert at position:

arr.insert(i, x) - Remove element:

arr.remove(x)orarr.pop() - Iterate:

for item in arr

Code example:

# Creating and using a list

numbers = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50]

# Fast indexed access

first = numbers[0] # 10

third = numbers[2] # 30

# Appending is efficient

numbers.append(60) # [10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60]

# Inserting in the middle is expensive (shifts elements)

numbers.insert(2, 25) # [10, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, 60]

# Iterating

for num in numbers:

print(num)

# Slicing (Python-specific)

subset = numbers[1:4] # [20, 25, 30]Common mistakes:

- Frequent middle insertions - Using arrays for frequent insertions in the middle causes performance issues. Consider linked lists or other structures.

- Index out of bounds - Accessing

arr[length]instead ofarr[length-1]causes errors. Always validate indices. - Assuming fixed size - Dynamic arrays can grow, but resizing has costs—pre-allocate capacity when size is known.

- Shallow vs deep copies - Copying arrays may create references, not new data. Understand your language’s copy semantics.

When to recognize them:

- Numeric indexing is used for access.

- Elements maintain order.

- Sequential iteration is common.

- Position matters for operations.

When NOT to use arrays: Don’t use arrays for frequent insertions in the middle (use linked lists), when you need key-based access (use hash maps), or when order doesn’t matter, and you need uniqueness (use sets).

Stacks

What they are: Last-in-first-out (LIFO) collections where elements are added and removed from one end.

Why they exist: Many problems require “most recent first” access. Function calls use call stacks, where the most recently called function must finish first. Undo operations reverse the last action first. Stacks solve reverse-order processing by restricting access to one end.

Mental model: Picture a stack of plates - you can only add or remove from the top. The last plate you put on is the first one you can take off.

Core properties:

- LIFO order - Last element added is first removed.

- Single access point - Operations happen at one end (the “top”).

- Push and pop - Add with push, remove with pop.

- No random access - Cannot access elements by index.

- Dynamic size - Grows and shrinks as elements are added or removed.

Where they appear:

- Python:

listused as stack –stack.append(x),stack.pop(). For concurrency, usequeue.LifoQueue. There is no built-inStackclass in the standard library. - JavaScript:

Arrayused as stack -stack.push(x),stack.pop()(push/pop operate on end, efficient) - Java:

Stackclass -new Stack<>()(legacy class, preferDequeinterface withArrayDeque) - C++:

std::stack-std::stack<int> s(container adapter, defaults to deque) - Go:

sliceused as stack -stack = append(stack, x),stack[len(stack)-1](append grows, efficient) - Rust:

Vecused as stack -stack.push(x),stack.pop()(returnsOption<T>, safe)

Common operations:

- Push:

stack.push(x)orstack.append(x) - Pop:

stack.pop() - Peek:

stack.top()orstack[-1] - Check empty:

stack.empty()orlen(stack) == 0

Code example:

# Using a list as a stack

stack = []

# Push elements (add to end)

stack.append(10)

stack.append(20)

stack.append(30)

# Stack: [10, 20, 30]

# Pop element (remove from end)

top = stack.pop() # Returns 30, stack: [10, 20]

# Peek without removing

if stack:

current = stack[-1] # 20, stack unchanged

# Check if empty

is_empty = len(stack) == 0Common mistakes:

- Using wrong end for operations - Stacks use one end only. Using

insert(0, x)instead ofappend(x)in Python creates an inefficient stack. - Accessing empty stack - Always check if the stack is empty before popping or peeking to avoid errors.

- Mixing stack and queue operations - Don’t use

pop(0)orshift()on stacks; that’s queue behavior. - Stack overflow - Deep recursion using the call stack can overflow. Use explicit stack structure for deep traversals.

When to recognize them:

- Last-in-first-out access pattern.

- Function call management (call stack).

- Expression evaluation.

- Undo/redo operations.

- Backtracking algorithms.

When NOT to use stacks: Don’t use stacks when you need first-in-first-out access (use queues), when you need random access to elements (use arrays), or when you need to access elements in the middle (use arrays or lists).

Queues

What they are: First-in-first-out (FIFO) collections where elements are added at one end and removed from the other.

Why they exist: Many systems process items in the order they arrive. Print queues, task schedulers, and message queues all require first-in-first-out processing. Queues enforce FIFO discipline at both ends.

Mental model: Picture a line at a coffee shop - the first person in line is the first person served. New people join at the back, service happens at the front.

Core properties:

- FIFO order - First element added is first removed.

- Two access points - Add at rear, remove from front.

- Enqueue and dequeue - Add with enqueue, remove with dequeue.

- No random access - Cannot access elements by index.

- Dynamic size - Grows and shrinks as elements are added or removed.

Where they appear:

- Python:

collections.dequeorqueue.Queue–from collections import deque(preferdequefor both queues and deques when you need O(1) operations at both ends;Queueis thread-safe) - JavaScript:

Arrayused as queue -queue.push(x),queue.shift()(shift() is O(n), inefficient for large queues) - Java:

Queueinterface,LinkedList-new LinkedList<>()(LinkedList is O(1) for both ends) - C++:

std::queue-std::queue<int> q(container adapter, defaults to deque) - Go:

sliceorcontainer/list-list.New()(slices are inefficient for queues, use container/list) - Rust:

VecDeque-use std::collections::VecDeque(double-ended queue, efficient)

Common operations:

- Enqueue:

queue.enqueue(x)orqueue.push(x) - Dequeue:

queue.dequeue()orqueue.pop()orqueue.shift() - Peek:

queue.front()orqueue[0] - Check empty:

queue.empty()orlen(queue) == 0

Code example:

from collections import deque

# Using deque as a queue (efficient)

queue = deque()

# Enqueue (add to rear)

queue.append(10)

queue.append(20)

queue.append(30)

# Queue: deque([10, 20, 30])

# Dequeue (remove from front)

front = queue.popleft() # Returns 10, queue: deque([20, 30])

# Peek without removing

if queue:

next_item = queue[0] # 20, queue unchanged

# Check if empty

is_empty = len(queue) == 0Common mistakes:

- Using array shift() for queues - JavaScript

Array.shift()is O(n) and inefficient. Use a proper queue implementation or a deque. - Wrong end operations - Queues add at the rear, remove from the front. Mixing ends breaks the FIFO guarantee.

- Not checking empty - Always verify the queue isn’t empty before dequeuing to avoid errors.

- Thread-safety assumptions - Regular queues aren’t thread-safe. Use thread-safe variants (like

queue.Queuein Python) for concurrent access.

When to recognize them:

- First-in-first-out access pattern.

- Task scheduling.

- Breadth-first search.

- Message processing.

- Print job queues.

When NOT to use queues: Don’t use queues when you need last-in-first-out access (use stacks), when you need random access (use arrays), or when you need to access elements by key (use hash maps).

Reflection: Think about the code you’ve written recently. Did you use arrays when a stack or queue might have been clearer? What access patterns did your code need?

Deques (Double-Ended Queues)

What they are: Queues that allow adding and removing elements from both ends.

Why they exist: Some problems require flexible end access - stack behavior (LIFO), queue behavior (FIFO), or both-end manipulation. Sliding window algorithms add at one end and remove from the other. Deques provide O(1) operations at both ends without middle access.

Core properties:

- Double-ended access - Operations at both front and rear.

- Flexible order - Can behave like a stack or a queue.

- Efficient operations - O(1) operations at both ends.

- No random access - Cannot access middle elements efficiently.

- Dynamic size - Grows and shrinks as needed.

Where they appear:

- Python:

collections.deque-from collections import deque(efficient O(1) operations at both ends) - JavaScript: Custom implementation or

Arraywith methods (no built-in deque, Array methods are inefficient) - Java:

ArrayDeque-new ArrayDeque<>()(preferred over Stack and LinkedList for most cases) - C++:

std::deque-std::deque<int> dq(chunked storage, good for large data) - Go:

container/list-list.New()(doubly-linked list, not true deque but similar) - Rust:

VecDeque-use std::collections::VecDeque(ring buffer implementation)

Common operations:

- Add front:

deque.appendleft(x)ordeque.push_front(x) - Add rear:

deque.append(x)ordeque.push_back(x) - Remove front:

deque.popleft()ordeque.pop_front() - Remove rear:

deque.pop()ordeque.pop_back()

Code example:

from collections import deque

# Creating a deque

dq = deque([1, 2, 3])

# Add to front

dq.appendleft(0) # deque([0, 1, 2, 3])

# Add to rear

dq.append(4) # deque([0, 1, 2, 3, 4])

# Remove from front

front = dq.popleft() # Returns 0, deque([1, 2, 3, 4])

# Remove from rear

rear = dq.pop() # Returns 4, deque([1, 2, 3])Common mistakes:

- Using Array for deque operations - JavaScript arrays don’t efficiently support front operations. Use a proper deque or a custom implementation.

- Confusing with queue/stack - Deques support both patterns, but aren’t automatically FIFO or LIFO. Document intended usage.

- Random access assumptions - Deques don’t efficiently support middle access. Use arrays if random access is needed.

When to recognize them:

- Need stack and queue operations.

- Sliding window problems.

- Palindrome checking.

- Both ends of the manipulation are needed.

When NOT to use deques: Don’t use deques when you need random access to middle elements (use arrays), when you only need one-end access (use stacks or queues), or when you need key-based access (use hash maps).

If you remember only one thing about linear structures: Arrays give you fast index access; stacks provide you with last-in-first-out; queues give you first-in-first-out. Choose based on how you need to pull things out.

Reflection Questions:

- Think about code you’ve written recently. Did you use arrays when a stack or queue might have been clearer? What access patterns did your code need?

- When would you choose a deque over a stack or queue? What problems require flexible end access?

- Quick check: You need to process items in reverse order of arrival. Which linear structure fits? (Answer: Stack - LIFO gives reverse order)

Section 3: Key-Value Structures

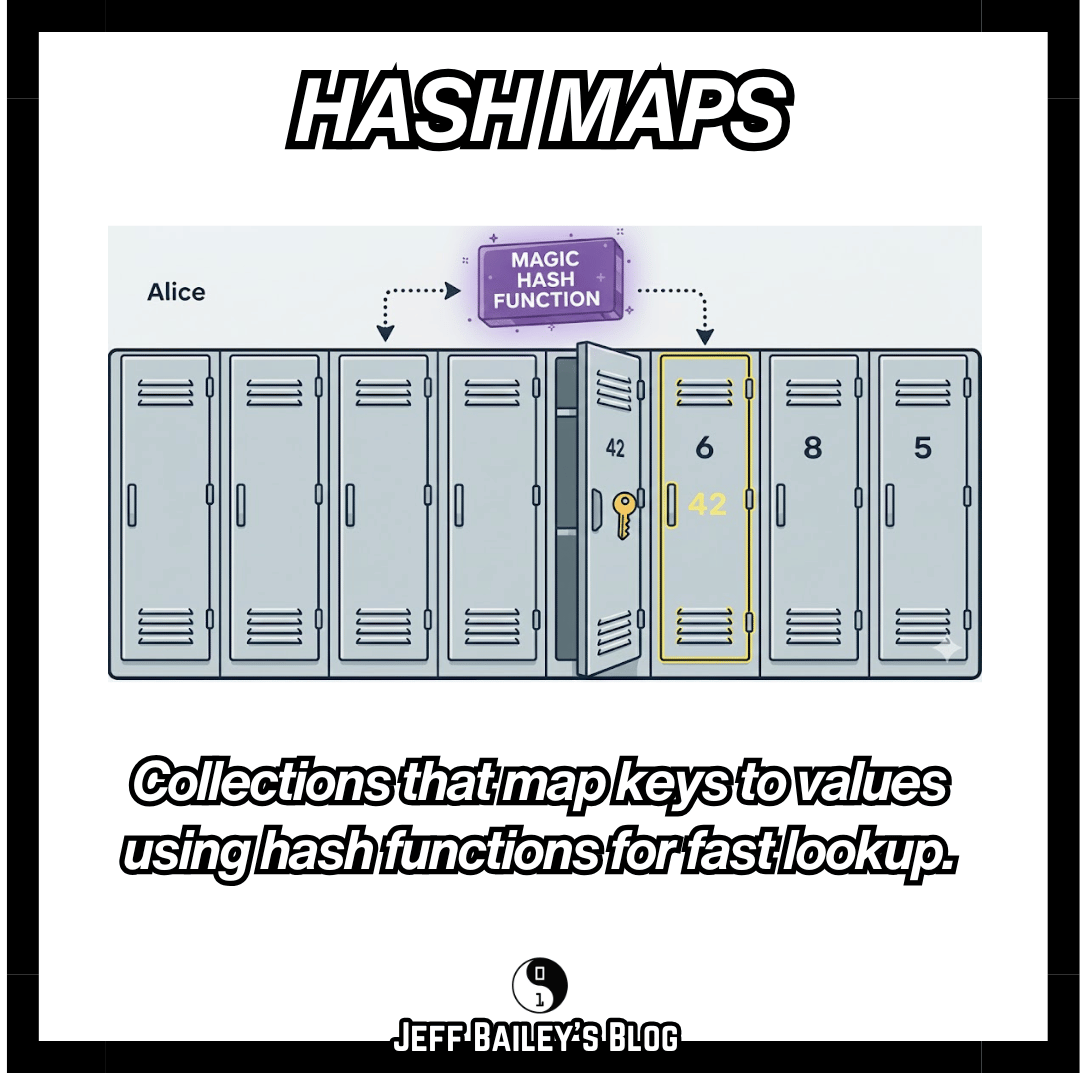

Hash Maps (Dictionaries, Maps, Objects)

What they are: Collections that map keys to values using hash functions for fast lookup.

Why they exist: Programs need fast lookups by name or identifier. Array searches take O(n) time. Hash maps use hash functions to compute array positions from keys, enabling O(1) average-case lookups. Hash functions work like a library’s card catalog - compute a shelf number from the title, then go directly to that shelf.

Mental model: Picture a hash map as a row of lockers with a “magic” function that picks the locker for a given name. Give it “Alice,” and it instantly tells you locker #42, no searching needed.

Core properties:

- Key-value pairs - Each element is a key mapped to a value.

- Fast lookup - Average O(1) access by key.

- Unique keys - Each key appears once.

- Unordered - Key order not guaranteed (language-dependent).

- Dynamic size - Grows as key-value pairs are added.

Where they appear:

- Python:

dict-{'key': 'value'}(maintains insertion order since Python 3.7, O(1) average case) - JavaScript:

ObjectorMap-{key: 'value'}ornew Map()(Map preserves insertion order, Object has prototype issues) - Java:

HashMap-new HashMap<>()(no order guarantee, use LinkedHashMap for order) - C++:

std::unordered_map-std::unordered_map<string, int> m(hash table, no order) - Go:

map-map[string]int{}(random iteration order, not thread-safe) - Rust:

HashMap-use std::collections::HashMap(no order, use BTreeMap for sorted) - Ruby:

Hash-{key: 'value'}(maintains insertion order since Ruby 1.9)

Common operations:

- Get value:

map.get(key)ormap[key] - Set value:

map.put(key, value)ormap[key] = value - Check key:

key in mapormap.containsKey(key) - Remove key:

map.remove(key)ordel map[key] - Iterate:

for key, value in map.items()

Code example:

# Creating a dictionary

user_data = {

"name": "Alice",

"age": 30,

"email": "alice@example.com"

}

# Fast key-based lookup

name = user_data["name"] # "Alice"

age = user_data.get("age", 0) # 30, with default if missing

# Setting values

user_data["city"] = "New York"

# Checking existence

if "email" in user_data:

print(user_data["email"])

# Iterating

for key, value in user_data.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")

# Counting occurrences

word_counts = {}

words = ["apple", "banana", "apple", "cherry"]

for word in words:

word_counts[word] = word_counts.get(word, 0) + 1

# Result: {"apple": 2, "banana": 1, "cherry": 1}Common mistakes:

- Assuming order - Many hash maps don’t guarantee order. Don’t rely on iteration order unless documented (Python 3.7+, JavaScript Map).

- Key type restrictions – Hash/set keys must be hashable, which means they have a stable hash and equality definition. Mutable built-ins like

listanddictare deliberately unhashable in Python, because if their contents changed while they were in a set or dict, lookups would break. - Collision performance - Poor hash functions or many collisions degrade to O(n). Use proper hash functions.

- Missing key errors - Accessing non-existent keys may raise errors. Use

get()with defaults or check existence first. - JavaScript Object vs Map - Objects have prototype pollution risks and string-only keys. Use Map for general key-value storage.

When to recognize them:

- Key-based lookups needed.

- Associative relationships.

- Caching data.

- Counting occurrences.

- Grouping by key.

When NOT to use hash maps: Don’t use hash maps when you need ordered iteration (use sorted structures), when you need range queries (use trees), when keys are not hashable/immutable, or when you only need to track membership without values (use sets).

Hash Sets

What they are: Collections that store unique elements using hash functions for fast membership testing.

Why they exist: Programs need fast membership testing - “have I seen this before?” or “is this item in my collection?” Array/list membership checks take O(n) time. Hash sets use the same hash function approach as hash maps but store only keys, providing O(1) average-case membership testing for duplicate detection, visited node tracking, and unique value storage.

Core properties:

- Unique elements - No duplicates allowed.

- Fast membership - Average O(1) to check if element exists.

- Unordered - Element order not guaranteed (language-dependent).

- No values - Stores only keys, not key-value pairs.

- Dynamic size - Grows as elements added.

Where they appear:

- Python:

set–{1, 2, 3}(mutable, no duplicates; iteration order should be treated as undefined for sets, even if some implementations appear to preserve insertion order) - JavaScript:

Set-new Set([1, 2, 3])(preserves insertion order, uses SameValueZero equality) - Java:

HashSet-new HashSet<>()(no order, use LinkedHashSet for order) - C++:

std::unordered_set-std::unordered_set<int> s(hash set, no order) - Go:

map[T]boolor custom implementation (no built-in set, map pattern is common) - Rust:

HashSet-use std::collections::HashSet(no order, use BTreeSet for sorted) - Ruby:

Set-require 'set'(requires require statement, not built-in)

Common operations:

- Add element:

set.add(x) - Remove element:

set.remove(x) - Check membership:

x in setorset.contains(x) - Union:

set1.union(set2) - Intersection:

set1.intersection(set2)

Code example:

# Creating a set

visited = {1, 2, 3}

# Fast membership testing

if 2 in visited:

print("Already visited")

# Adding elements

visited.add(4)

visited.add(2) # No duplicate, set unchanged

# Removing elements

visited.remove(1)

# Set operations

set1 = {1, 2, 3, 4}

set2 = {3, 4, 5, 6}

union = set1.union(set2) # {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}

intersection = set1.intersection(set2) # {3, 4}

difference = set1.difference(set2) # {1, 2}

# Removing duplicates from a list

numbers = [1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4]

unique = list(set(numbers)) # [1, 2, 3, 4]Common mistakes:

- Assuming order - Sets are unordered in most languages. Don’t rely on iteration order.

- Mutable elements – Hash/set keys must be hashable, which means they have a stable hash and equality definition. Mutable built-ins like

listanddictare deliberately unhashable in Python, because if their contents changed while they were in a set or dict, lookups would break. - Equality semantics - JavaScript Set uses SameValueZero (NaN equals NaN), which differs from

===. - Using lists for membership - Checking

x in listis O(n). Use sets for O(1) membership testing. - Go map pattern - Using

map[T]boolas a set works, but isn’t as clear. Consider documenting the pattern.

When to recognize them:

- Duplicate elimination needed.

- Fast membership testing.

- Set operations (union, intersection).

- Tracking visited elements.

- Unique value storage.

When NOT to use hash sets: Don’t use hash sets when you need ordered elements (use sorted sets), when you need to store key-value pairs (use hash maps), when elements are not hashable/immutable, or when you need range queries (use trees).

Reflection Questions:

- Have you ever used a list to check membership (

if x in list)? How would using a set change the code and performance? - Quick check: When would a hash set be better than a hash map for tracking visited items? (Hint: Do you actually need a value attached to each key?)

Key-Value Structures Summary:

- Hash maps provide fast key-based lookups with associated values

- Hash sets provide fast membership testing without values

- Both use hash functions for O(1) average-case operations

- Choose maps when you need values, sets when you only need presence

Reflection Questions:

- Quick check: You need to track which users have logged in today, but don’t need any additional data about them. Which structure fits? (Answer: Hash set - membership testing without values)

- When would you choose a HashMap over an array of key-value pairs? What’s the performance difference?

- For a deeper comparison between lists and sets for membership testing, see the reflection questions at the end of the Hash Sets section.

Section 4: Hierarchical Structures

Linear structures handle sequence-like data. Many systems organize information hierarchically, where relationships follow a parent-child pattern rather than a sequential order.

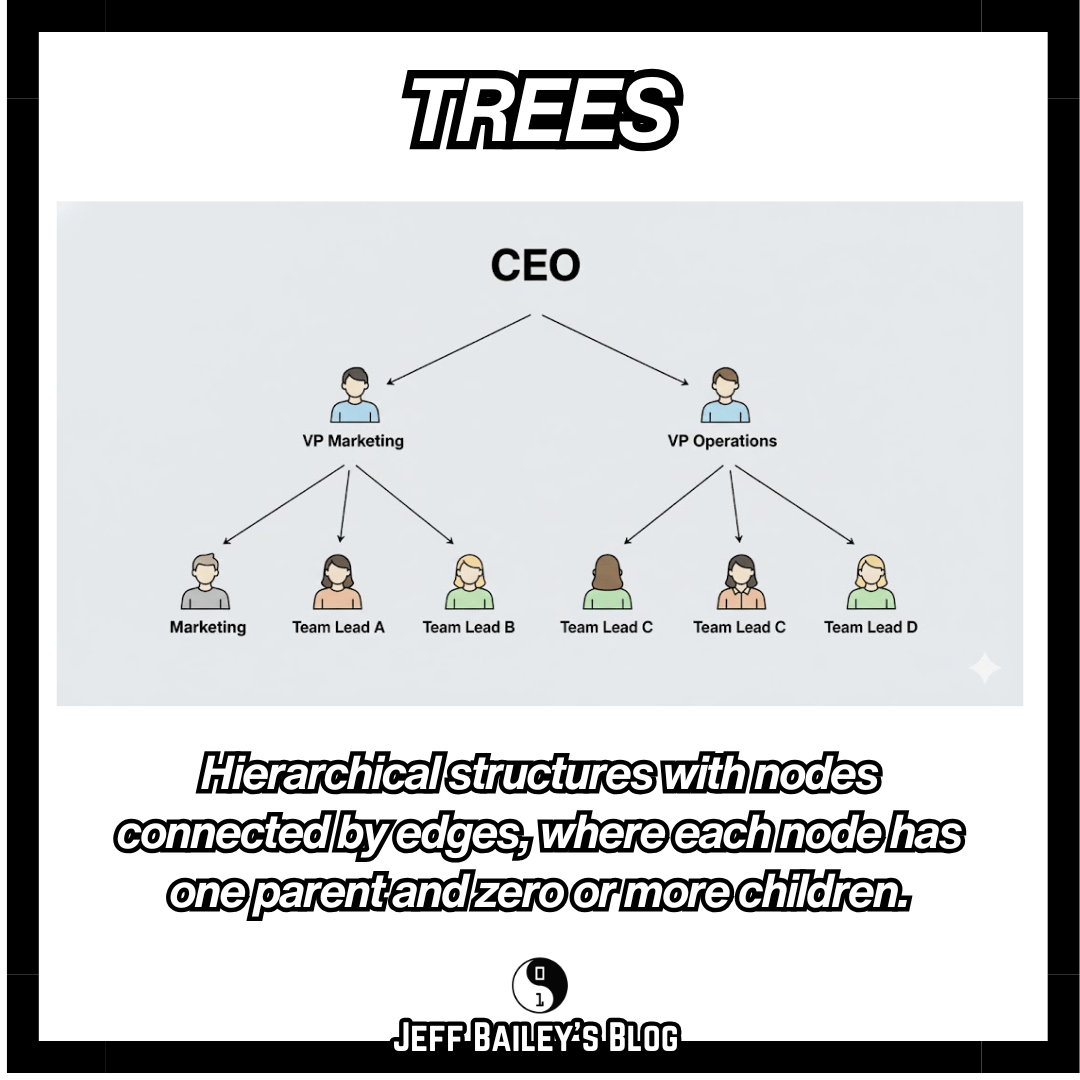

Trees

What they are: Hierarchical structures with nodes connected by edges, where each node has one parent and zero or more children.

Why they exist: Many real-world relationships are hierarchical. File systems, organization charts, and expression trees all follow parent-child patterns. Trees organize information like a company org chart: the CEO is the root, departments are children, and teams are grandchildren. The single-parent constraint prevents cycles, making traversal predictable and efficient.

Mental model: Picture a tree as an organizational chart where each person reports to exactly one manager (except the CEO). This structure prevents confusion - you always know who reports to whom.

Core properties:

- Hierarchical - Parent-child relationships.

- Root node - One node with no parent.

- Leaf nodes - Nodes with no children.

- No cycles - Cannot form loops.

- Single parent - Each node has exactly one parent (except the root).

Where they appear:

- Python: Custom classes or

collections(no built-in tree). - JavaScript: Custom classes or libraries.

- Java: Custom classes or

TreeMap,TreeSetfor binary search trees. - C++:

std::map,std::set(red-black trees) or custom classes. - Go: Custom structs and pointers.

- Rust: Custom structs with

BoxorRc.

Note: Many “sorted map” or “sorted set” types in standard libraries are implemented as self-balancing binary search trees (e.g., red-black trees, AVL trees).

Common tree types:

- Binary trees - Each node has at most two children.

- Binary search trees - Sorted binary trees for fast lookups.

- N-ary trees - Nodes can have multiple children.

- Tries - Trees for string storage and prefix matching.

Common operations:

- Insert node:

tree.insert(value) - Search:

tree.find(value) - Traverse: Pre-order, in-order, post-order, level-order.

- Delete node:

tree.delete(value)

Conceptual example:

Trees organize data hierarchically. A file system is a tree: folders contain subfolders and files. Each folder has one parent (except the root) and can have multiple children. This structure prevents cycles and makes navigation predictable.

Advanced Implementation Notes:

Tree implementation example (click to expand)

This example illustrates the tree structure, not the best-practice implementation. For production code, use language-provided tree structures or established libraries.

# Simple tree node structure

class TreeNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.children = []

# Creating a tree

root = TreeNode("A")

root.children = [TreeNode("B"), TreeNode("C")]

root.children[0].children = [TreeNode("D"), TreeNode("E")]

# Tree traversal (pre-order)

def traverse(node):

if node is None:

return

print(node.value) # Process node

for child in node.children:

traverse(child) # Recurse on children

traverse(root) # Prints: A, B, D, E, CCommon mistakes:

- No cycle detection - Trees shouldn’t have cycles, but code might create them. Validate tree structure.

- Stack overflow - Deep recursion on unbalanced trees can overflow the call stack. Use iterative traversal or limit depth.

- Missing null checks - Always check if the node is None before accessing children to avoid errors.

- Assuming balanced - Unbalanced trees degrade performance. Use self-balancing trees (AVL, red-black) when needed.

When to recognize them:

- Hierarchical data representation.

- File system structures.

- Organization charts.

- Expression trees.

- Decision trees.

When NOT to use trees: Don’t use trees when you need flexible many-to-many relationships (use graphs), when you need fast key-based lookups without hierarchy (use hash maps), or when data is flat with no relationships (use arrays or lists).

Binary Search Trees

What they are: Binary trees where the left child values are less than the parent, and the correct child values are greater.

Why they exist: Binary search trees combine sorted array ordering with dynamic tree insertion/deletion. Unlike sorted arrays, insertion and deletion are O(log n). Unlike hash maps, BSTs provide ordered iteration and range queries. BSTs maintain ordering through a tree structure rather than an array position.

Core properties:

- Sorted order - In-order traversal produces a sorted sequence.

- Fast search - O(log n) average case for balanced trees.

- Binary structure - Each node has at most two children.

- Ordering invariant - Left < Parent < Right maintained.

- Balance matters - Unbalanced trees degrade to O(n) performance.

Where they appear:

- Python:

sortedcontainerslibrary or custom implementation. - JavaScript: Custom implementation or libraries.

- Java:

TreeMap,TreeSet-new TreeMap<>() - C++:

std::map,std::set-std::map<int, string> m - Go: Custom implementation.

- Rust:

BTreeMap,BTreeSet-use std::collections::BTreeMap

Common operations:

- Insert:

bst.insert(value) - Search:

bst.find(value) - Delete:

bst.delete(value) - Minimum/Maximum:

bst.min(),bst.max() - Range queries:

bst.range(low, high)

Conceptual example:

BSTs maintain sorted order through a tree structure. Imagine a phone book organized as a BST: names less than “M” go left, names greater go right. This organization enables fast searches by eliminating half the remaining possibilities at each step.

Advanced Implementation Notes:

BST implementation example (click to expand)

This example illustrates BST structure and search logic, not a production-ready implementation. For production code, use language-provided sorted structures or established libraries.

# Binary search tree node

class BSTNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.left = None

self.right = None

# Search in BST

def search(root, value):

if root is None or root.value == value:

return root

if value < root.value:

return search(root.left, value)

return search(root.right, value)

# Insert in BST

def insert(root, value):

if root is None:

return BSTNode(value)

if value < root.value:

root.left = insert(root.left, value)

else:

root.right = insert(root.right, value)

return rootCommon misconceptions:

“BSTs always guarantee O(log n) performance” - Reality: Only self-balancing BSTs (AVL, red-black) guarantee O(log n). Regular BSTs can degrade to O(n) with sorted input, creating a linked-list-like structure. Always use self-balancing variants when performance matters.

“BSTs are faster than hash maps for lookups” - Reality: Hash maps are O(1) average case, BSTs are O(log n). Use BSTs when you need ordering or range queries, not for pure lookup speed.

“Any traversal gives sorted order” - Reality: Only in-order traversal produces sorted sequence. Pre-order and post-order traversals don’t maintain sorted order.

Common mistakes:

- Unbalanced trees - Inserting sorted data creates linked-list-like tree with O(n) performance. Use self-balancing variants.

- Duplicate handling - BSTs typically don’t allow duplicates or handle them inconsistently. Define behavior explicitly.

- Complex deletion - Deleting nodes with two children requires finding a successor. Implementation can be error-prone.

- Assuming sorted - Only in-order traversal gives sorted order. Other traversals don’t.

When to recognize them:

- Sorted data needed.

- Range queries required.

- Ordered iteration is essential.

- Fast insertion and deletion with ordering.

When NOT to use binary search trees: Don’t use BSTs when you don’t need ordering (use hash maps), when data arrives pre-sorted (unbalanced BSTs degrade to O(n)), when you need guaranteed O(log n) performance (use self-balancing trees), or when you only need fast lookups without ordering (use hash maps).

Heaps (Priority Queues)

What they are: Complete binary trees that maintain the heap property (parent greater than/less than children).

Why they exist: Many systems process items by priority rather than by arrival order. Task schedulers, event simulators, and algorithms like Dijkstra’s need priority-ordered access. Heaps maintain the min/max at the root while allowing efficient O(log n) insertion and extraction.

Core properties:

- Heap property - Parent nodes greater (max-heap) or less (min-heap) than children.

- Complete tree - All levels filled except possibly last, filled left to right.

- Fast access - O(1) access to min/max element.

- Efficient insertion - O(log n) insertion.

- Priority ordering - Highest/lowest priority element always at root.

Where they appear:

- Python:

heapqmodule -import heapq - JavaScript: Custom implementation or libraries.

- Java:

PriorityQueue-new PriorityQueue<>() - C++:

std::priority_queue-std::priority_queue<int> pq - Go:

container/heap-import "container/heap" - Rust:

BinaryHeap-use std::collections::BinaryHeap

Common operations:

- Insert:

heap.push(value) - Extract min/max:

heap.pop() - Peek:

heap.top()orheap[0] - Build heap:

heapify(array)

Code example:

import heapq

# Python heapq creates a min-heap by default

heap = []

heapq.heappush(heap, 5)

heapq.heappush(heap, 2)

heapq.heappush(heap, 8)

heapq.heappush(heap, 1)

# Heap: [1, 2, 8, 5] (min at root)

# Get minimum

min_val = heapq.heappop(heap) # Returns 1, heap: [2, 5, 8]

# Peek without removing

if heap:

next_min = heap[0] # 2, heap unchanged

# Build heap from list

numbers = [3, 1, 4, 1, 5, 9, 2, 6]

heapq.heapify(numbers) # In-place heapifyCommon misconceptions:

“Heaps are sorted arrays” - Reality: Heaps only guarantee that the root is min/max. Other elements aren’t sorted. Only the root is efficiently accessible. Use sorted structures if you need all elements in order.

“Heaps are always faster than sorted arrays” - Reality: Heaps excel at priority queue operations (O(log n) insert/extract), but if you need sorted iteration or frequent access to all elements, sorted arrays or BSTs may be better.

“All heaps are min-heaps” - Reality: Most libraries default to min-heaps, but max-heaps exist. Understand your library’s default and how to create max-heaps (often by negating values or using comparators).

Common mistakes:

- Max-heap confusion - Most libraries provide min-heap. For a max heap, negate values or use a custom comparator.

- Index assumptions - Only root (index 0) is guaranteed min/max. Other elements aren’t sorted.

- Not a sorted array - Heaps don’t provide sorted iteration. Only the root is accessible efficiently.

- Python list as heap - Don’t modify heap list directly. Always use heapq functions to maintain the heap property.

When to recognize them:

- Priority queue needed.

- K most significant/smallest elements.

- Scheduling with priorities.

- Event simulation.

- Dijkstra’s algorithm.

When NOT to use heaps: Don’t use heaps when you need sorted iteration (only root is accessible efficiently), when you need random access (use arrays), when you need key-based lookups (use hash maps), or when you need all elements in sorted order (use sorted structures).

Hierarchical Structures Summary:

- Trees organize data with parent-child relationships and no cycles

- Binary search trees provide sorted data with efficient insertion/deletion

- Heaps provide priority-ordered access with efficient min/max extraction

- All hierarchical structures enable efficient traversal following relationships

Reflection Questions:

- Quick check: You need to process tasks by priority (highest first), but don’t need all tasks sorted. Which structure fits? (Answer: Heap - provides priority queue with O(1) access to the highest priority)

- When would you choose a BST over a HashMap? What trade-offs are you making?

- Think about a file system. Why is it a tree structure? What would break if it were a graph instead?

Section 5: Graph Structures

Hierarchical structures enforce single-parent relationships. Graphs remove these constraints to model flexible, many-to-many connections found in networks, dependencies, and social relationships.

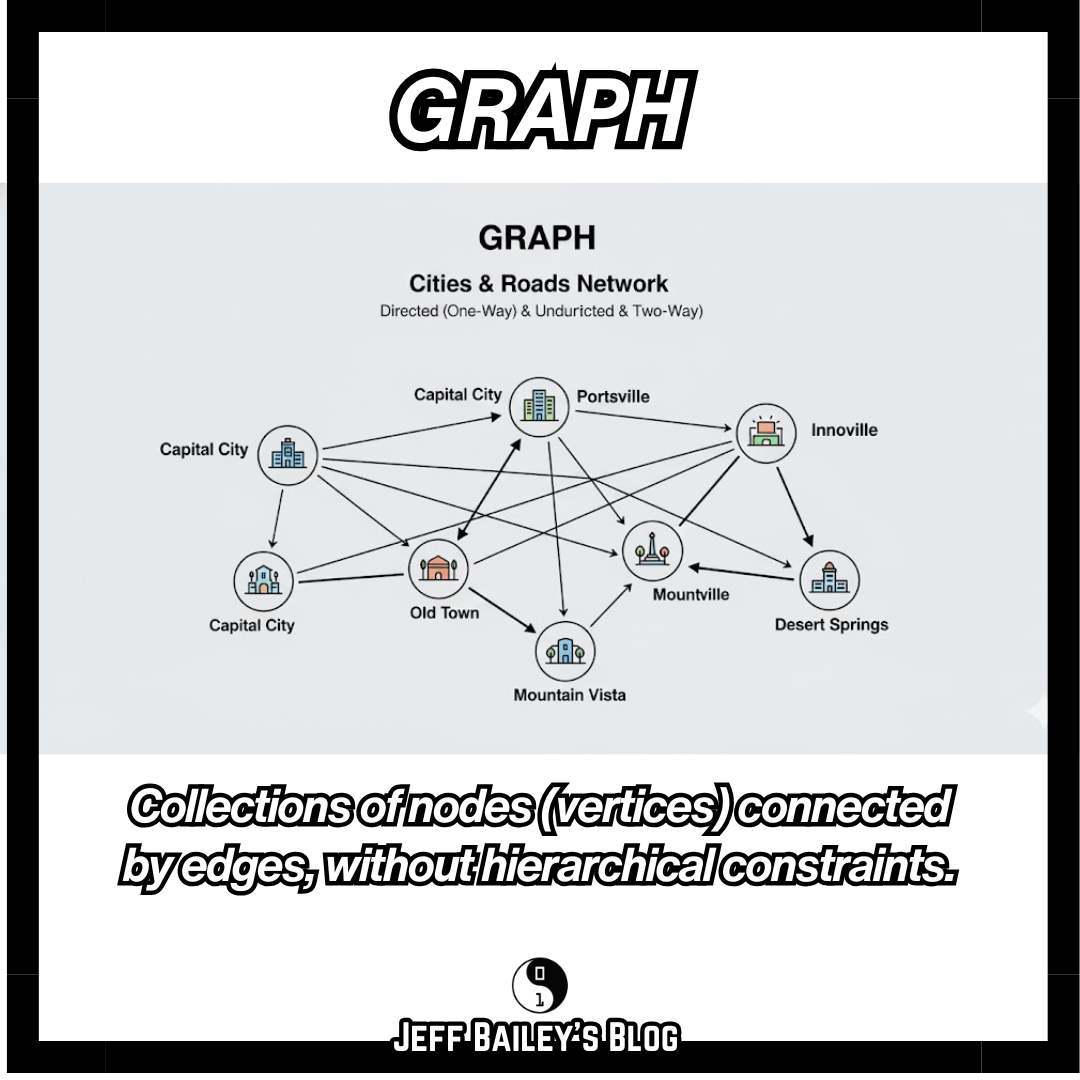

Graphs

What they are: Collections of nodes (vertices) connected by edges, without hierarchical constraints.

Why they exist: Graphs exist because many relationships don’t fit hierarchical structures. Social networks model friendships where people can be friends with many others who are also friends with each other. Road networks connect cities in complex ways. Dependency graphs show how components depend on each other.

Mental model: A graph is a map of cities with roads. Any city can connect to any other, and routes can be one-way (directed) or bidirectional (undirected). Unlike trees, there’s no single “root,” and cities can form loops.

Quick comparison: Trees are graphs with no cycles and exactly one parent per node. Graphs drop those constraints so you can model any connection pattern.

Core properties:

- Nodes and edges - Vertices connected by relationships.

- Flexible connections - No parent-child restrictions.

- Cycles allowed - Can form loops.

- Directed or undirected - Edges may have direction.

- Weighted or unweighted - Edges may have associated weights.

Where they appear:

- Python: Custom classes,

networkxlibrary -import networkx as nx - JavaScript: Custom classes or libraries like

graphlib. - Java: Custom classes or libraries like JGraphT.

- C++: Custom classes or Boost Graph Library.

- Go: Custom structs with adjacency lists or matrices.

- Rust: Custom structs or crates like

petgraph.

Common representations:

- Adjacency list - Each node stores a list of neighbors.

- Adjacency matrix - 2D array where

matrix[i][j]indicates edge. - Edge list - List of all edges as pairs.

Common operations:

- Add vertex:

graph.add_vertex(v) - Add edge:

graph.add_edge(u, v) - Traverse: Depth-first search, breadth-first search.

- Shortest path: Dijkstra’s, Bellman-Ford algorithms.

- Cycle detection: Detect if cycles exist.

Code example:

# Graph using adjacency list

from collections import defaultdict

class Graph:

def __init__(self):

self.graph = defaultdict(list)

def add_edge(self, u, v):

self.graph[u].append(v)

# For an undirected graph, also add: self.graph[v].append(u)

def dfs(self, start, visited=None):

if visited is None:

visited = set()

visited.add(start)

print(start)

for neighbor in self.graph[start]:

if neighbor not in visited:

self.dfs(neighbor, visited)

# Usage

g = Graph()

g.add_edge(0, 1)

g.add_edge(0, 2)

g.add_edge(1, 2)

g.add_edge(2, 3)

g.dfs(0) # Traverses graph starting from 0Common misconceptions:

“Graphs are just complex trees” - Reality: Trees are graphs with restrictions (no cycles, single parent). Graphs remove these constraints to model flexible relationships. The key difference: graphs allow cycles and multiple parents, making traversal more complex.

“All graph algorithms work the same on directed and undirected graphs” - Reality: Directed and undirected graphs have different properties. Algorithms like shortest path behave differently. Always verify whether your graph is directed or undirected before choosing algorithms.

“Adjacency matrices are always better” - Reality: Adjacency matrices use O(V²) space and are only efficient for dense graphs. Adjacency lists are better for sparse graphs (most real-world graphs). Choose based on graph density.

Common mistakes:

- Cycle infinite loops - Graphs can have cycles. Always track visited nodes to prevent infinite traversal.

- Memory for dense graphs - Adjacency matrices use O(V²) space. Use adjacency lists for sparse graphs.

- Directed vs undirected - Confusing directed and undirected graphs leads to incorrect algorithms.

- No path exists - Not all nodes are reachable. Handle disconnected components.

When to recognize them:

- Network relationships.

- Social networks.

- Dependency graphs.

- Route finding.

- Recommendation systems.

When NOT to use graphs: Don’t use graphs when relationships are strictly hierarchical (use trees), when you only need simple key-value lookups (use hash maps), when data has no relationships (use arrays or lists), or when you need guaranteed acyclic structures (use trees or DAGs—Directed Acyclic Graphs, which are a special case of graphs used for topological sorting, build systems, and dependency resolution).

Reflection Questions:

- Quick check: What’s the key difference between a tree and a graph that makes trees easier to traverse? (Answer: Trees have no cycles and a single parent per node, making traversal predictable)

- Think about social networks. Why are they graphs rather than trees? What relationships would break the tree constraint?

- When would you choose an adjacency list over an adjacency matrix? What factors influence this choice?

Section 6: Specialized Structures

Linked Lists

What they are: Sequences of nodes where each node contains data and a reference to the next node.

Why they exist: Arrays require shifting all subsequent elements for middle insertions/deletions, which is O(n). Linked lists store elements in separate nodes connected by pointers, enabling middle insertions by updating pointers rather than moving data. This trades random access for efficient middle insertions/deletions.

Core properties:

- Node-based - Elements stored in separate nodes.

- Dynamic size - Grows and shrinks easily.

- Sequential access - Must traverse from start to reach element.

- No random access - Cannot jump to the index directly.

- Flexible allocation – Allocates nodes individually as needed, avoiding large contiguous blocks, but with pointer overhead and weaker cache locality than arrays.

Where they appear:

- Python: Custom classes or

collections.deque(doubly-linked internally). - JavaScript: Custom classes.

- Java:

LinkedList-new LinkedList<>() - C++:

std::list-std::list<int> l - Go:

container/list-list.New() - Rust: Custom structs with

BoxorRc.

Common types:

- Singly-linked - Each node points to the next only.

- Doubly-linked - Each node points to the next and the previous.

- Circular - Last node points back to first.

Common operations:

- Insert at head:

list.prepend(value) - Insert at tail:

list.append(value) - Remove:

list.remove(value) - Traverse: Iterate from head to tail.

Conceptual example:

Linked lists store elements in separate nodes connected by pointers. Think of a treasure hunt where each clue points to the following location. Unlike arrays, where all items are in one place, linked list items can be scattered in memory, connected only by these pointers.

Advanced Implementation Notes:

Linked list implementation example (click to expand)

This example illustrates linked list structure and pointer manipulation, not a production-ready implementation. Most languages provide linked list implementations in standard libraries.

# Simple linked list node

class ListNode:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

self.next = None

# Linked list operations

class LinkedList:

def __init__(self):

self.head = None

def prepend(self, value):

new_node = ListNode(value)

new_node.next = self.head

self.head = new_node

def append(self, value):

new_node = ListNode(value)

if self.head is None:

self.head = new_node

return

current = self.head

while current.next:

current = current.next

current.next = new_node

def traverse(self):

current = self.head

while current:

print(current.value)

current = current.nextCommon misconceptions:

“Linked lists are always better than arrays for insertions” - Reality: Linked lists excel at middle insertions when you already have a pointer to the insertion point. But finding that point is O(n). Arrays are often better suited to append-heavy workloads due to better cache locality and a more straightforward memory layout.

“Linked lists use less memory than arrays” - Reality: Linked lists have pointer overhead (8 bytes per node in 64-bit systems). Arrays have no pointer overhead. For small elements, arrays may use less total memory.

“Linked lists are faster because they don’t need to shift elements” - Reality: While true for middle insertions, arrays benefit from CPU cache locality. Sequential array access is much faster than jumping through pointer-chased linked list nodes. Modern CPUs optimize for contiguous memory access.

Common mistakes:

- Losing references - When inserting/deleting, update pointers correctly, or you’ll lose parts of the list.

- Null pointer errors - Always check if node is None before accessing

nextto avoid errors. - Circular references - Accidentally creating cycles makes traversal infinite. Validate list structure.

- Inefficient operations - Finding tail for append is O(n). Keep tail pointer for O(1) appends.

When to recognize them:

- Frequent insertions/deletions in the middle.

- Unknown size at creation.

- Implementing stacks or queues.

- Memory-efficient sequential access.

When NOT to use linked lists: Don’t use linked lists when you need random access by index (use arrays), when you need cache-friendly access patterns (arrays are better), when memory overhead matters (pointers add overhead), or when you primarily append/access from ends (arrays or deques are better).

Strings

What they are: Sequences of characters, often implemented as arrays or specialized structures.

Strings are included here because they behave like specialized arrays and are fundamental in every language. While strings are often implemented as character arrays, they’re treated as a fundamental type because text manipulation has unique requirements: encoding (e.g., UTF-8, UTF-16), immutability (in many languages), and specialized operations (concatenation, searching, pattern matching). Strings solve the problem of storing and manipulating sequences of characters with language-specific optimizations for text processing.

Core properties:

- Character sequence - Ordered collection of characters.

- Immutable or mutable - May or may not allow in-place modification (language-dependent).

- Indexed access - Can access characters by position.

- String operations - Concatenation, slicing, searching built-in.

- Encoding aware - May handle Unicode, UTF-8, etc.

Where they appear:

- Python:

str(immutable) -"hello" - JavaScript:

String(immutable) -"hello" - Java:

String(immutable),StringBuilder(mutable) -"hello" - C++:

std::string(mutable) -std::string s = "hello" - Go:

string(immutable) -"hello" - Rust:

String,&str-String::from("hello")

Common operations:

- Concatenate:

str1 + str2 - Slice:

str[start:end] - Find:

str.find(substring) - Replace:

str.replace(old, new) - Split:

str.split(delimiter)

Code example:

# String operations

text = "Hello, World!"

# Concatenation (creates a new string if immutable)

greeting = "Hello" + ", " + "World!" # New string

# Slicing

substring = text[0:5] # "Hello"

last_word = text[-6:] # "World!" (negative indexing)

# Finding

index = text.find("World") # 7, or -1 if not found

# Replacing (creates a new string)

new_text = text.replace("World", "Python") # "Hello, Python!"

# Splitting

parts = text.split(", ") # ["Hello", "World!"]

# Joining

words = ["Hello", "World"]

joined = ", ".join(words) # "Hello, World"Common misconceptions:

“String concatenation is always O(1)” - Reality: In languages with immutable strings (Python, JavaScript, Java), concatenation creates new strings, making repeated concatenation O(n²). Use

join()or string builders for multiple concatenations.“Strings are just character arrays” - Reality: While strings are often implemented as character arrays, they have unique properties: immutability (in many languages), encoding awareness (UTF-8, UTF-16), and specialized operations. Treating them as simple arrays can lead to encoding bugs.

“All languages handle strings the same way” - Reality: String mutability, encoding, and memory representation vary significantly. Python strings are immutable and Unicode-aware. C++ strings are mutable. Rust has both

String(owned) and&str(borrowed). Understand your language’s model.

Common mistakes:

- Inefficient concatenation - Repeated

str1 + str2creates many temporary strings. Usejoin()for multiple concatenations. - Mutability assumptions - Most languages have immutable strings. Operations return new strings, don’t modify in place.

- Encoding issues - Strings may be bytes or Unicode. Understand your language’s string model (UTF-8, UTF-16, etc.).

- Index out of bounds - String indices can be out of range. Validate indices before access.

When to recognize them:

- Text processing.

- Pattern matching.

- String manipulation.

- Parsing and tokenization.

When NOT to use strings: Don’t use strings when you need to store binary data (use byte arrays), when you need mutable character sequences (use string builders or character arrays), or when you need numeric operations (use numeric types).

Reflection Questions:

- Quick check: You need to concatenate 1000 strings. In a language with immutable strings, what’s the most efficient approach? (Answer: Use

join()or a string builder - repeated concatenation creates many temporary strings) - Think about the text processing you’ve done. Did you treat strings as arrays? What encoding issues might arise?

- When would you choose a string builder over regular string concatenation? What’s the performance difference?

Section 7: Structure Recognition in Code

How to identify structures

When reading code, look for these patterns to identify data structures:

Arrays/Lists:

- Numeric indexing:

arr[0],arr[i] - Sequential iteration:

for item in arr - Length property:

len(arr),arr.length

Hash Maps:

- Key-value access:

map[key],map.get(key) - Key iteration:

for key in map - Key existence checks:

key in map

Sets:

- Membership testing:

x in set - No value access: Only keys, no

set[key] - Set operations:

union,intersection

Stacks:

- Last-in operations:

push(),pop() - Single-end access: Only the top element is accessed.

- LIFO pattern: Last added, first removed.

Queues:

- Two-end operations:

enqueue(),dequeue() - FIFO pattern: First added, first removed.

- Front/rear access: Different ends for add/remove.

Trees:

- Node references:

node.left,node.right,node.children - Recursive traversal: Functions that call themselves on children.

- Hierarchical access: Parent-child relationships.

Graphs:

- Edge lists: Collections of

(u, v)pairs. - Adjacency structures: Nodes storing neighbor lists.

- Traversal algorithms: DFS, BFS patterns.

Quick Check – Tree vs Graph: What’s the key difference between a tree and a graph that makes trees easier to traverse? Hint: what constraints do trees have that graphs don’t?

Language-specific naming

The same structure may have different names:

- Hash map: Dictionary (Python), Object/Map (JavaScript), HashMap (Java), unordered_map (C++), map (Go).

- Array: List (Python), Array (JavaScript/Java), vector (C++), slice (Go), Vec (Rust).

- Set: Set (Python/JavaScript/Java), unordered_set (C++), HashSet (Rust).

Focus on properties, not names. A structure that maps keys to values is a hash map, regardless of the language’s naming conventions.

Section 8: Choosing Structures

Comparing Similar Structures

When multiple structures seem to fit your problem, understanding their differences helps you choose the right one. These comparisons highlight key trade-offs:

Stacks vs Queues

Stacks (LIFO): Last-in-first-out. Use when you need reverse-order processing: function calls, undo operations, backtracking.

Queues (FIFO): First-in-first-out. Use when you need arrival-order processing: task scheduling, message queues, breadth-first search.

Key difference: Stacks process most recent first; queues process oldest first.

Hash Maps vs Binary Search Trees

Hash Maps: O(1) average lookups, no ordering. Use for fast key-based access when order doesn’t matter.

BSTs: O(log n) lookups, maintains sorted order. Use when you need ordered iteration or range queries.

Key difference: Hash maps prioritize speed; BSTs prioritize ordering.

Arrays vs Linked Lists

Arrays: Fast index access (O(1)), cache-friendly, but slow middle insertions (O(n)). Use for sequential access patterns.

Linked Lists: Fast middle insertions when you have a pointer (O(1)), but slow access (O(n)). Use for frequent middle modifications.

Key difference: Arrays optimize access; linked lists optimize middle insertions.

Hash Sets vs Hash Maps

Hash Sets: Store only keys, fast membership testing. Use when you only need to track presence: visited nodes, unique values.

Hash Maps: Store key-value pairs and provide fast key-based lookups. Use when you need associated data, such as user preferences and configurations.

Key difference: Sets track membership; maps store associations.

Heaps vs Sorted Arrays

Heaps: O(1) access to min/max, O(log n) insert/extract. Use for priority queues when you only need the top element.

Sorted Arrays: O(log n) search, O(n) insert, but all elements accessible. Use when you need sorted iteration or frequent access to all elements.

Key difference: Heaps optimize priority access; sorted arrays optimize sorted iteration.

Trees vs Graphs

Trees: Hierarchical, no cycles, single parent. Use for file systems, organization charts, and expression trees.

Graphs: Flexible connections, cycles allowed, multiple parents. Use for social networks, dependency graphs, and route finding.

Key difference: Trees enforce hierarchy; graphs allow flexible relationships.

Structure Selection Workflow

When choosing a data structure, follow this systematic process:

- Identify access patterns - How will you access data? By position, by key, by priority?

- List required operations - Insert, delete, search, iterate? Which are most frequent?

- Consider data characteristics - Ordered? Unique? Hierarchical? Networked?

- Check time complexity - Use the complexity table to verify operations match your needs

- Consider language specifics - Some languages have quirks (JavaScript

Array.shift()is O(n)) - Start simple, optimize later - Begin with the simplest structure that works

Memory aid: “Access, Operations, Characteristics, Complexity, Language, Simple” (AOC-CLS)

Quick decision flow:

- Need to access by index? → Array/List

- Need key-based lookup? → Hash Map / Map

- Need uniqueness only? → Set

- Need FIFO/LIFO? → Queue / Stack

- Need hierarchy? → Tree

- Need arbitrary connections? → Graph

Time complexity quick reference

The following cards compare the typical time and space complexities of common operations across fundamental data structures. Use this to verify that your chosen structure’s operations match your performance needs:

Array/List

- Access: O(1)

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: amortized O(1) end, O(n) middle

- Delete: O(n) end, O(n) middle

- Space: O(n)

Note: Dynamic arrays grow occasionally, so appends are amortized O(1) but worst-case O(n) during resize.

Stack

- Access: O(1) top

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: O(1)

- Delete: O(1)

- Space: O(n)

Queue

- Access: O(1) front

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: O(1)*

- Delete: O(1)*

- Space: O(n)

Assuming a proper queue implementation (linked list, deque, ring buffer). Naïve array-based queues that use shift() or pop(0) are O(n).

Deque

- Access: O(1) ends

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: O(1) ends

- Delete: O(1) ends

- Space: O(n)

Hash Map

- Access: O(1) avg

- Search: O(1) avg

- Insert: O(1) avg

- Delete: O(1) avg

- Space: O(n)

Hash Set

- Access: N/A

- Search: O(1) avg

- Insert: O(1) avg

- Delete: O(1) avg

- Space: O(n)

Binary Search Tree

- Access: O(log n) avg

- Search: O(log n) avg

- Insert: O(log n) avg

- Delete: O(log n) avg

- Space: O(n)

Heap

- Access: O(1) root

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: O(log n)

- Delete: O(log n)

- Space: O(n)

Linked List

- Access: O(n)

- Search: O(n)

- Insert: O(1) known pos

- Delete: O(1) known pos

- Space: O(n)

Graph

- Access: Varies

- Search (traversal): O(V+E)

- Insert/Delete vertex/edge: typically O(1)–O(degree) with adjacency lists

- Space: O(V+E)

Complexity depends on representation (adjacency list vs matrix) and operation type.

Note: “avg” indicates average case. Worst case may differ (e.g., hash map collisions, unbalanced BST).

Quick selection guide

Need ordered, indexed access?

- Use arrays/lists for sequential data with position-based access.

Need fast key-based lookup?

- Use hash maps for key-value relationships.

Need unique elements only?

- Use hash sets for membership testing without values.

Need last-in-first-out?

- Use stacks for LIFO access patterns.

Need first-in-first-out?

- Use queues for FIFO access patterns.

Need hierarchical relationships?

- Use trees for parent-child structures.

Need flexible connections?

- Use graphs for network relationships.

Need priority ordering?

- Use heaps for priority queue operations.

Quick Decision Scenarios:

You’re building a task scheduler that processes tasks in arrival order. Which structure fits? (Answer: Queue - FIFO processing matches arrival order)

You need to find the 5 largest numbers from a stream of 1 million numbers. Which structure fits? (Answer: Heap - maintains top K elements efficiently)

You’re tracking which users have viewed a page, but don’t need any additional data. Which structure fits? (Answer: Hash set - membership testing without values)

You need to store user preferences keyed by user ID with fast lookups, but order doesn’t matter. Which structure fits? (Answer: Hash map - O(1) key-based lookups, no ordering needed)

Common structure combinations

Real programs often combine structures:

- Hash map of arrays - Grouping items by key.

- Array of hash maps - Records with key-value fields.

- Tree with hash map cache - Hierarchical data with fast lookups.

- Stack of hash maps - Scoped variable storage.

Understanding individual structures helps you recognize and design these combinations.

Evaluating your current data structure choices

Before troubleshooting, evaluate whether your structure choice is working:

- Ask: Which operations dominate? (Lookups, inserts, deletes, scans?)

- Measure: Use simple timers or profilers on hot paths to identify bottlenecks.

- Inspect: Look for suspicious patterns (e.g., lots of

insert(0, …)on arrays, orx in listwhen a set would be better). - Experiment: Swap in an alternative (e.g., list → deque, map → ordered map) and compare performance.

This evaluation connects the complexity table, selection workflow, and troubleshooting guidance into a cohesive decision-making path.

Section 9: Troubleshooting Common Issues

These troubleshooting patterns map directly to the Structure Selection Workflow (Section 8) and the Complexity Table. Use them together to diagnose and resolve structure-related issues.

Problem: Structure performance doesn’t match expectations

Symptoms:

- Operations that should be fast are slow.

- Performance degrades unexpectedly as data grows.

- Code works with small data but fails with significant inputs.

Solutions:

- Verify time complexity - Check if you’re using the proper structure for your access patterns. Arrays aren’t efficient for frequent middle insertions.

- Profile operations - Use profiling tools to identify which operations are slow. The bottleneck might not be where you expect.

- Check for hidden operations - Some operations trigger hidden work (e.g., array resizing, hash map rehashing). Understand amortized costs.

- Review language implementation - Some language implementations have quirks. JavaScript

Array.shift()is O(n), not O(1).

Problem: Structure behaves differently across languages

Symptoms:

- Code works in one language but fails in another.

- The iteration order differs unexpectedly.

- Operations that work in one language cause errors in another.

Solutions:

- Understand language semantics - Python dicts maintain order since 3.7, but Java HashMaps don’t. Read language documentation.

- Check for language-specific types - JavaScript has both

ObjectandMap. Understand when to use each. - Validate assumptions - Don’t assume all languages implement structures identically. Test behavior, don’t assume.

Problem: Memory usage grows unexpectedly

Symptoms:

- Memory consumption increases over time.

- Structures consume more memory than expected.

- System runs out of memory with moderate data sizes.

Solutions:

- Check for unbounded growth - Hash maps and caches can grow without limits: set capacity limits or eviction policies.

- Understand structure overhead - Linked structures have pointer overhead. Arrays have contiguous memory but may overallocate.

- Monitor structure sizes - Add logging to track structure sizes over time. Identify which structures grow unexpectedly.

- Use appropriate structures - Don’t use hash maps for small, fixed datasets. Arrays might be more memory-efficient.

Problem: Structure operations cause errors

Symptoms:

- Accessing elements raises index errors.

- Null pointer exceptions when accessing structure elements.

- Operations fail on empty structures.

Solutions:

- Validate before access - Always check if the structure is empty before accessing elements. Check bounds before array access.

- Handle missing keys - Use safe access methods (

get()with defaults) instead of direct key access that may raise errors. - Initialize properly - Ensure structures are initialized before use. Some languages require explicit initialization.

- Understand error semantics - Different languages handle missing keys differently. Python raises

KeyError, JavaScript returnsundefined.

Problem: Choosing between similar structures

Symptoms:

- Multiple structures fit the problem.

- Unclear which structure to use for a specific use case.

- Performance differences between similar structures are unclear.

Solutions:

- Identify access patterns - List the operations you need (insert, delete, search, iterate) and their frequencies.

- Consider data size - Small datasets might not show performance differences. Choose for clarity over micro-optimization.

- Review time complexity table - Use the complexity reference to understand trade-offs between structures.

- Start simple, optimize later - Begin with the simplest structure that works. Optimize only if profiling shows it’s needed.

Self-Assessment: Test Your Understanding

Before moving on, test your understanding:

Structure Selection: You need to store user preferences keyed by user ID, with fast lookups. Which structure fits? Why?

- Answer guidance: Hash maps provide O(1) key-based lookups, perfect for user ID → preferences mapping.

Property Recognition: You see code using

push()andpop()on an array. What structure pattern is this? What are the performance implications?- Answer guidance: This is a stack pattern. If using the correct end (i.e., the last element), it’s O(1). If using the wrong end, it’s O(n).

Trade-off Analysis: When would you choose a binary search tree over a hash map? What are the trade-offs?

- Answer guidance: Choose BSTs when you need ordered iteration or range queries. Trade-off: BSTs are O(log n) vs hash maps’ O(1), but provide ordering.

Language Recognition: You see

std::unordered_mapin C++ code. What fundamental structure is this? What properties does it have?- Answer guidance: This is a hash map. Properties: key-value pairs, O(1) average lookup, no order guarantee, unique keys.

Problem-Solution Matching: What structure solves the problem of “I need to process tasks in the order they arrive”?

- Answer guidance: A queue provides first-in-first-out (FIFO) processing, perfect for task scheduling in arrival order.

Structure Relationships

These fundamental structures form a cohesive toolkit for organizing data. Understanding how they relate helps you see the bigger picture:

Arrays are building blocks - Many other structures use arrays internally. Hash maps use arrays for buckets, heaps use arrays for storage, and strings are often character arrays.

Hash maps use hash functions - Hash maps solve the “fast lookup by key” problem by using hash functions to compute array positions, combining arrays with hash functions.

Trees are restricted graphs - Trees are graphs with the constraint of no cycles and a single parent per node. This restriction makes traversal predictable and efficient.

Stacks and queues are access patterns - These aren’t separate storage mechanisms but access patterns that can be implemented with arrays or linked lists, depending on performance needs.

Sets are simplified maps - Hash sets use the same hash function approach as hash maps, but store only keys, solving the “membership testing” problem efficiently.

Understanding these relationships helps you see why specific structures exist and when to combine them to solve complex problems.

Future Trends: Fundamentals Remain Constant

While programming languages evolve, fundamental data structures remain constant:

New languages, same structures - Rust, Go, and modern languages still provide arrays, hash maps, and trees. The structures are universal because they solve universal problems.

Implementation improvements - Hash maps get better collision handling, trees get better balancing algorithms, but properties stay the same. O(1) hash map lookups remain O(1) even as implementations improve.

Specialized variants - New structures like skip lists or bloom filters build on fundamentals. Understanding fundamentals helps you learn these variants quickly.

Performance optimizations - Cache-friendly layouts, memory pooling, and SIMD optimizations improve performance but don’t change fundamental properties. Arrays are still O(1) access, just faster.

The structures described in this article will remain fundamental in 20 years because they solve universal problems. What changes is how languages expose them and how implementations optimize them.

Conclusion

The Complete Catalog of Structure Types

This catalog has covered the fundamental data structure types found in most programming languages. Each type exists because it solves a specific problem by optimizing certain operations:

- Linear structures (arrays, stacks, queues, deques) handle sequential data with different access patterns

- Key-value structures (hash maps, sets) enable fast lookups by key or membership testing

- Hierarchical structures (trees, BSTs, heaps) organize relationships and priorities

- Graph structures model flexible, many-to-many connections

- Specialized structures (linked lists, strings) solve specific problems efficiently

The Unifying Framework: Choose Based on Operations

All data structures answer one fundamental question: which operations must be fast? The three-axes mental model—access pattern, update pattern, relationship pattern—helps you see why each structure type exists and when to choose each one:

- Arrays optimize index access at the cost of middle insertions

- Hash maps optimize key lookups at the cost of ordering

- Trees optimize hierarchical relationships at the cost of lookup speed

- Stacks optimize last-in access at the cost of random access

- Heaps optimize priority access at the cost of sorted iteration

Understanding when each type fits—based on which operations dominate your use case—helps you choose the right structure type for each problem.

Key Takeaways

- Fundamental data structure types exist because they solve universal problems – Organizing data efficiently for different access patterns.

- Structure type names vary across languages, but properties remain constant – Recognize types by properties, not names.

- Each structure type optimizes different operations – Linear types (arrays, stacks, queues) handle sequential data; key-value types (hash maps, sets) provide fast lookups; hierarchical types (trees, heaps) organize relationships; graph types model flexible connections.

- Choose based on use cases – Identify which operations must be fast, then pick the structure type that optimizes those operations.

- Every structure type makes trade-offs – There’s no “best” type, only the right type for your problem.

- Real programs combine structure types – Complex problems require combining multiple types.

Recognize these structure types in code you read and write. Frequent exposure builds an intuitive structure-selection mechanism based on operational requirements and use cases, rather than memorized rules.

Getting Started & Next Steps

Getting started (today):

- Refactor one small function to use a more appropriate structure.

- Look at the code you wrote recently. Which fundamental structures did you use? Could you have chosen different structures?

Next week:

- Read code in different languages and identify structures by properties, not names.

- Practice structure recognition - identify structures in code you encounter.

Longer term:

- Pair this catalog with Fundamentals of Data Structures to connect structure types with effective usage in software.

- Study language documentation to learn how your languages implement these structure types.

- Build small projects using different structure types to solve problems.

Recognize fundamental structure types in daily coding to build intuition.

Related Articles

Related fundamentals articles:

Data Structures: Fundamentals of Data Structures covers how to use data structures effectively in software—performance, reliability, and system design.

Algorithms: Fundamentals of Algorithms explains how algorithms work with data structures to process information efficiently.

Software Engineering: Fundamentals of Software Design helps you understand how design principles inform structure selection.

Glossary

Array: A contiguous, indexed sequence of elements. Provides O(1) access by position but O(n) insertion or deletion in the middle.

Binary search tree: A tree where each node's left children are smaller and right children are larger. Supports O(log n) search, insert, and delete when balanced.

Deque: A double-ended queue that supports insertion and removal at both ends in O(1) time.

FIFO: First In, First Out. The access pattern of a queue: the earliest added element is removed first.

Graph: A structure of nodes (vertices) connected by edges. Models relationships like networks, dependencies, and routes.

Hash collision: When two distinct keys map to the same hash table slot. Resolved by chaining (linked lists) or open addressing (probing).

Hash map: A key-value store using a hash function for O(1) average lookup, insert, and delete. Also called dictionary, map, or associative array.

Hash set: An unordered collection of unique elements using hashing for O(1) average membership testing.